The House that Slavery Built: The normalization of racial terror

by Lucy Duncan, all images by the author

A painting of General William Sherman and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton meeting with 20 Black residents of Savannah, mostly ministers, at the end of the civil war. Based on what they shared, two weeks later Sherman issued Field Order 15 which called for redistribution of land to those formerly enslved, more widely known as 40 acres and a mule. Read more here.

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” James Baldwin

Recently I visited Savannah, Georgia with a dear friend of mine. Our first full day there, the incomparable Sistah Patt Gunn took us on a private Slaves in the City tour with her daughter Imani. We started out on the river at the African American monument depicting an African American family with broken chains at their feet, it is inscribed with these words by Maya Angelou,

“We were stolen, sold and bought together from the African Continent. We got on the slave ships together, we lay back to belly in the holds of the slave ships in each other's excrement and urine together. Sometimes died together and our lifeless bodies thrown overboard together. Today we are standing up together with faith and even some joy.”

There was a lot of push back from the Black mayor for including these words on the monument, but eventually the originators of the project prevailed with the inclusion of the last line added by Angelou.

We looked at the river, there was a giant riverboat at the spot where slave ships would disembark (there is no marker there) and there is a salt stained plaque describing the history of enslavement. Georgia was founded by James Oglethorpe who brought many people to the colony released from debtors’ prison. He believed people should work with their own labor and hold smaller tracts of land, so slavery was outlawed for the first 16 years of the colony until 1751 even though enslaved people were “borrowed” or “hired out” from nearby slave states to build Georgia. On the marker is an image of a manifest of enslaved people on the Gustavus Schooner, with people listed for the price they would be auctioned for. Sistah Patt shared how the price for enslaved people was calculated - a combination of how many children they might bear, plus the skills they brought as they arrived in Savannah.

Stones paving the street adjacent to city hall that were ballast stones from slave ships.

We walked up the street just a few feet from the river. We stood on cobblestones that paved the way to city hall. Sistah Patt said that when the enslavers brought enslaved people to Savannah, they had to balance their boats with stones to serve as ballast. When they disembarked the people they brought into slavery they also took the ballast stones off the ship, and used them as paving stones. We were standing on stones the weight of Sistah Patt’s and other folks in Savannah’s enslaved ancestors. People regularly steal the stones and sell them as relics of slavery, and the city has yet to install a way to record the theft and hold those who take them accountable. Amidst the stones are embossed bricks with place names on them, these mark graves of enslaved people.

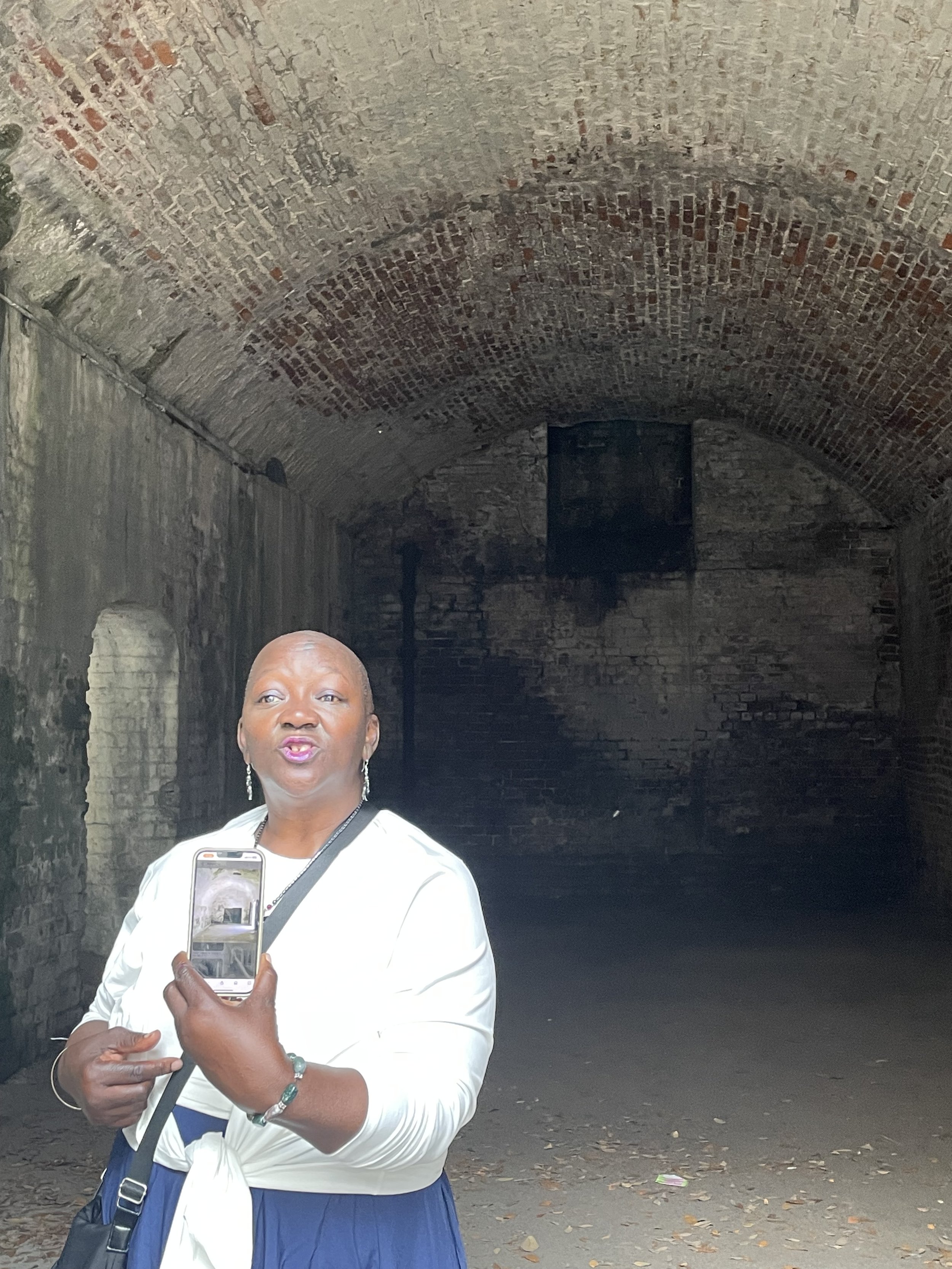

Sister Patt showing the enclosures in Savannah that were used as holding slaves for the enslaved and sharing an image of similar holding cells in Ghana.

We turned the corner and stopped at large brick rooms with curved ceilings. There were three of them on this road. Sistah Patt said they were holding cells for the enslaved folks after they had disembarked from the slave ships. Each cell is marked with a label, the signage claims these are part of a retaining wall to hold back the Savannah River if it floods but none of them indicate these were holding cells of enslaved people. Despite significant evidence the city continues to deny the true purpose of these rooms. Sistah Patt showed us an image of almost identical structures in Ghana near the spaces that enslaved Africans disembarked and showed us markings of different African tribes on the bricks of the cells.

A cell that held enslaved people before auction just adjacent to city hall in Savannah.

Then she sang for us a song that rice planters and reapers would sing so that they could keep themselves from developing hernias from the hard labor they endured. Folks went by and listened in to Patt’s stories as we stood there, as she countered many of the common stories told to obfuscate the reality of this history that happened really not so long ago, that built the city and this country out of racial terror and genocide.

We walked up the hill and Sistah Patt showed us the public whipping wall just up the street from the holding cells. There are hooks still in the walls and markings of the remnants of this terror. The city denies the truth of this wall as well.

A witness tree in Johnson Square.

We turned the corner to Johnson Square in the center of the city. Sistah Patt pointed out the slave auction block which is dominated by an obelisk marking the tomb of Nathanael Greene, who owned hundreds of slaves on his nearby Mulberry Grove Plantation. She told us the story of the weeping time, the largest auction of enslaved people in U.S. history, two days in which over 400 people were auctioned off to pay the enslaver Pierce Mease Butler’s gambling debt. She pointed out the live oak trees around the square and that none of them has spanish moss growing on them, a rarity. She said that Gullah Geechee came and offered prayers and rituals on the occasion of the weeping time, and since that day no moss has grown on what she called the witness trees.

Sistah Patt pointed out the banks and insurance companies and churches around the square that were created in large part to support slavery: banks deemed enslaved people as collateral for loans, reinforcing their legal and delusional status as property; insurance companies offered policies in case of the death of enslaved people . St. John’s Episcopal Church, also on the square, had ties to slavery; many of the founders and early parishioners were enslavers.

There was the institution of slavery and all that arose from its conception and cruelty to reinforce its perpetuation.

Patt and Imani took us to the site of the Weeping Time. It has not rained while we were walking downtown, Sistah Patt said it doesn’t really rain for her tours, but as we drove to west Savannah and the site of the weeping time, it started to rain, hard. Sistah Patt said that for the two days of the weeping time, torrential rain fell, tears flowing from the sky for so many families being ripped apart on that day, for such an act of horrific cruelty. We drove past a marker of the weeping time, where there is a carousel of names, Sistah Patt said they have obtained funding to properly honor the site. We drove past the site of the old race track where the actual auction happened, where there is old machinery there, and it looks relatively abandoned.

Sistah Patt worked for years to get Calhoun Square, one of the many squares in Savannah, named after John C. Calhoun, an enslaver who was a staunch advocate for slavery and states rights, renamed Susie King Taylor Square. Susie King Taylor was the first Black civil war nurse and after the war she opened schools for African Americans in Savannah and Midway. This square and George Whitefield Square (also named after an enslaver) are believed to have been built on the sites of burial grounds of enslaved people, another way the lives and remains of formerly enslaved are desecrated and rendered invisible.

We visited the Owens Thomas House and Slave [sic] Quarters. It’s evident the space was reinterpreted to make the lives of those enslaved on the property more visible, and the opulence of the space and the emphasis on how the enslavers lived still feels like an obfuscation of the violence, terror of the place. We started out in the carriage house, which was a place the enslaved lived and worked. This house museum holds one of the most well preserved urban slave dwellings in any city. On the first floor was the kitchen and space in which the enslaved worked.

The ceiling is painted a deep blue, haint blue, a color that the Gullah Geechee understood as repelling ghosts and evil spirits.

On the second floor is where the enslaved lived, with a small bed, and very spare furnishings. It’s likely ten or more enslaved people lived cramped in this room, serving the enslavers. Those who lived there included the butler, the nanny, the cook and several others including enslaved children. The haint blue felt like a prayer on the ceiling, an expression of resistance and assertion of autonomy in the midst of an enclosure.

I asked the docent racialized as white whether he knew of descendants of those who were enslaved at this place, if folks had visited. He said they didn’t, that while he’d been there descendants had not identified themselves to him or to other docents as far as he knew. The museum had in mind a research project to identify some of the descendants, but it was shelved when the pandemic hit. I asked whether they had any documents or narratives from those who were enslaved there. He said he did not know of any, that there were letters about the life of enslaved people in the house written by George Owens which detail torture enacted on the enslaved in response to resistance, but generally not writings by those who were enslaved. There was one panel with writing by William Grimes, formerly enslaved who wrote an autobiography after he was freed and wrote about the brutal conditions in the Savannah slave jail, which was more commonly used for social control in urban settings than on plantations to obfuscate the torture.

Each place we visited in Savannah, I asked about the lives of the enslaved, and each place knew a little bit, but said for the most part they couldn’t document or verify the lives of the enslaved so they could not add that narrative much to their interpretation of the past. The intentional obfuscation perpetuates the intentional obfuscation.

Walking around Savannah with the azaleas in bloom, and jasmine perfuming the air, with the squares full of life and the teeming and pulsing of people walking in the city, I felt the weight of the way this place, and the United States, were built on genocide, lives constrained and brutalized, the theft of labor, and the torture of so many souls. This reality is just beneath the surface everywhere, perhaps more evident in overtly slave states, but it shapes the current reality so deeply, whether in segregated neighborhoods impacted by redlining, or the way downtowns (like Savannahs) are often more full with white folks and even in Black majority cities, you often must travel to the surrounding neighborhoods to see Black and POC folks not in service or working roles. In Philadelphia the slave auction block was at the corner of Market and Front Streets and in 1684 a ship, Isabella, arrived in Philadelphia with about 150 enslaved Africans, many held in bondage by Quaker enslavers. In 1688 was what was considered the first white protest against slavery, the Germantown declaration, which was rejected by the Quakers who continued to enslave people until the 1770s. In Philadelphia this legacy is often obfuscated even more than in Savannah.

The racial terror that founded this country has migrated to prisons, policing, deeply segregated schooling, and genocidal wars overseas, but the literal ground on which we walk is drenched in the blood of folks brutalized and subject to the violence of colonialism, racial capitalism, and white supremacy. Having been to Gaza twice, since October 7th it is always on my mind, holding the duel truths of staying connected to friends far away facing bombing and excruciating levels of terror, feeling the fog of grief for children and whole families decimated, while living in my days, being in community, spending time with resistors and dreamers and world makers. It can be dizzying. As a descendant of enslavers, I feel the weight of that lineage and the need to grapple with it and what it demands of me to work to make that legacy right, to work for the truth to be told, for repair to occur, for us to face the reality of the past so we can co-create a quite different future.

And even within the biased narrative we encountered most places we went, there were small narratives and demonstrations of resistance, and expansive spirits despite the brutality. The carriage house ceiling painted haint blue, the narratives of enslaved at the Owens Thomas House visiting friends after hours, the Gullah Geechee women enacting prayers and rituals on the occasion of the Weeping Time, and I am sure much bolder acts of resistance. Sistah Patt’s work to rename Calhoun Square after Susie King Taylor is an example of this bold resistance as she works for state-wide reparations initiatives as well.

An Adinkra symbol on the old cotton exchange building in Savannah.

Sistah Patt pointed out Adinkra symbols in buildings and in public spaces all over Savannah. Adinkra symbols are visual representations of philosophical ideas which express the beliefs and values of the Akan people of west Africa. The usually enslaved workers would cast prayers and cultural resistance into the spaces they created for this slaveholding city.